| Religio Seluciana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Indigenous Selucian religion |

| Theistic philosophy | Polytheistic |

| Supreme divinity | Sol Lucidus, Terra Mater, Neflons |

| Major Pantheon | Divine Pantheon |

| Minor Pantheon | Numerous minor divinities |

| Holy City | Auroria, Assedo, Argona |

| Scripture | Selucian mythology and folklore |

| Pontifex Maxima | Mallia Hesychia |

| Headquarters | Argona, Sadaria |

| Liturgical language | Classical Selucian |

Religio Seluciana (Selucian for "Selucian Religion"), also known as Cultus Deorum Selucianorum ("Worship of the Selucian Gods") or Selucian Paganism, is an indigenous and polytheistic Selucian religion. A follower of the Religion is known as a Cultor Deorum ("Worshipper of the Gods") or informally and (sometimes) offensively as a Paganus ("Peasant" or "Heathen"). The Selucian Religion is most notable in its contractual practice, in that dogma and faith are irrelevant within the Religio, whereas the proper practice of ritual and sacrifice is essential in securing the gods' favour, following a principle of do ut des ("I give that you may give"). Religio Seluciana is not a single organized faith, and there is much diversity in belief and practice from region to region and even from one individual to another. Over the centuries, the Religio has received many foreign influences from other polytheistic religions, such as that of the ancient Kalopians, Cildanians, or Irkawans as well as from Qedarite religions, primarily Hosianism, and Jelbic mythology, including its modern incarnation as Felinism.

History[]

Origins[]

Selucian Paganism is not a revealed faith, thus it does not have a single point of origin. Selucian mythology developed out of common proto-Superseleyan myths, with most gods in the Selucian pantheon having similar names and attributes with their equivalents in other Superseleyan mythologies.

Classical Antiquity[]

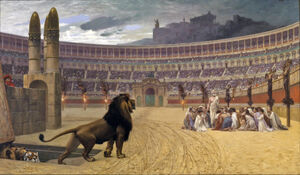

Ancient Selucian sacrifice

In the ancient Selucian city-states, politics and religion were closely connected. In most city-states, religion and government were dominated by an educated, male, landowning military aristocracy, and all official business was conducted under the auspices of the gods. During this time each city-state had its own deities, however there were also a number of pan-Selucian gods and goddesses. During the Selucian-Cildanian Wars the Selucian League was formed under the protection of Neflons, the god of the sea, and his temple in Assedo became the official meeting place for the Selucian assembly. It was also during this period that many foreign gods were introduced into the Selucian pantheon and adopted under a Selucianized form, most of them of Kalopian, Cildanian, or Irkawan origin.

Cildanian Hegemony[]

Representation of Sol Lucidus during the Cildanian Hegemony

When the Cildanian Hegemony conquered Selucia in 280 BCE, the previous syncretic trend continued much more intensely. There was significant interraction between Selucian, Cildanian, and Kalopian mythologies during this time; most notably, solar god Sol Lucidus, later to become the supreme divinity of the Selucian pantheon, was introduced as the Selucian version of Cildanian god El Shamash. Mystery cults also originate from this era, taken over from Kalopian religious practices with numerous Qedarite and indigenous elements. Under Cildanian rule, the Selucian gods received much official support, as the Empire was supportive of syncretic attempts to equate Selucian and Cildanian divinities, and many new temples were built during this era.

Late Antiquity and Middle Ages[]

After the fall of the Cildanian Hegemony in 22 CE, the Selucian religion entered a slow decline; with the islands divided into numerous city-states, and lacking the official patronage that the Empire provided, the temples fell into neglect. Additionally, the indigenous faith soon entered competition with the newly founded religion of Hosianism, which was brought on the islands by Apostle Michael in the 1st century. Hosianism gradually displaced the old polytheistic religion as the faith of the upper class, and by the 6th century it was established as the official religion of the majority of Selucian city-states and Selucia was recognised as the international headquarters of the entire Hosian Church after the Council of Auroria. Native beliefs and practices did nonetheless survive, mostly in rural areas, leading to the faith becoming known as "Paganism" (from paganus meaning "peasant"). Although there were a number of attempts at reviving the religion during Medieval times, they were generally unsuccessful.

Renascentia[]

Renascentia painting of the Birth of Futua

The rediscovery of classical mythology during the Renascentia led to a strong resurgence of Selucian Paganism beginning with the 15th century. As a consequence of newfound interest in the writings of ancient Selucians, Pagan writers could now rightfully point out that their faith, until that point looked down upon as nothing more than peasant superstition, had a rich and ancient philosophical tradition that could compete with Hosian theology on equal footing. The rebirth of Paganism during the Renascentia was however opposed by the Church, which also claimed itself the heir of ancient Selucian heritage by pointing out monotheistic tendencies within the writings of a number of classical philosophers. The Renascentia consequently became fertile ground for philosophical and theological disputes between the two competing traditions. The religious landscape of the archipelago was from this point on characterized by a relative balance between two religions, each with its own claim to higher intellectual and moral respectability.

Selucian Unification[]

By the late 18th century Paganism had become a central feature of Selucian nationalism, championed by the rising middle class dissatisfied with monarchic rule in the Selucian city-states and with the dominance of Hosianism, seen as a foreign faith and an impediment to unification. The Unification of Selucia, started and led by the newly created Republic of Argona, led to the creation of a unified Selucian Republic under Pagan leadership. When the Arch-Patriarchal state of Auroria, ruled by the Hosian Church, fell to Argonan armies and an internal uprising in 1811, the Treaty of Capitulation guaranteed a set of rights to the Hosians, including religious tolerance and fair treatment in return for their surrender and capitulation. However, a Hosian uprising in 1815 caused the Pagan side to consider that the Hosians had violated the Treaty, which gave them a justification for revoking its provisions. A series of laws were passed gradually restricting the rights of Hosians, by ordering the destruction of Hosian scriptures and places of worship, forbidding Hosians from assembling for worship, removing their judicial protection, and ordering the arrest and imprisonment of all bishops and priests. The persecution culminated in the Horatian Law (Lex Horatia de Hosiis) of 1818, that ordered all persons, men, women, and children, to gather in a public space and offer a collective sacrifice. If they refused, they were to be executed. These persecutions led to the almost complete elimination of the Holy Apostolic Hosian clergy, including the Arch-Patriarchy (the last Arch-Patriarch was executed in 1819), driving Hosianism underground. Deprived of the central leadership of the Church and believing Apostolic Succession and the See of St. Michael to have been brought to an end by the persecutions, the branches of the Church outside Selucia became independent national churches, thus putting an end to the Holy Apostolic Hosian Church of Terra.

Execution of Hosians after Unification

Simultaneously with the persecution of Hosianism, the religious policy of united Selucia also focused on creating a unified form of Selucian Paganism. An official pantheon was recognized, formed of 27 gods that included both pan-Selucian divinities and prominent local deities, and the College of Pontiffs was established as the governing body of the religion. Religious scriptures were standardized and a uniform system of worship was adopted for the entire nation. At the same time, Pagan practices that fell outside the scope of the official state cult were suppressed; mystery cults in particular were outlawed and persecuted, due to their perceived foreign character and accusations of immorality. These acts transformed the Religio from a heterogeneous collection of ethnic cultural and religious traditions into the national Selucian religion and the official faith of the united Imperium.

Decline[]

The apparent triumph of Paganism in the aftermath of the Unification did not last for long. Although deprived of its leadership and presumed extinct by the wider Hosian world, Hosianism continued to be practiced in secret in Selucia. Many Hosians avoided the requirement of sacrificing to the gods by bribing officials in order to gain a certificate attesting that they had offered sacrifice, without, however, having actually done so; others did in fact sacrifice to the gods but nonetheless continued Hosian worship. In the modern era restrictions on Hosianism gradually decreased, and by 2385 Hosians were sufficiently tolerated to elect the first Arch-Patriarch in centuries, thus founding the Selucian Patriarchal Church, although the other Hosian Churches rejected the legitimacy of this action since they believed continuity with the ancient Arch-Patriarchy had been broken.

As the Selucian Patriarchal Church began gaining adherents Terra-wide, partly due to the abuses of the Deltarian Church, its influence within and without Selucia was slowly rising, gradually shifting the balance of power away from Paganism. The Selucian Patriarchal Party, the political wing of the Church, became the largest faction in the Imperium, paralleling the gradual demographic increase in the number of Hosians, and in 2569 the party was powerful enough to replace Paganism with Selucian Patriarchalism as the state church of the nation.

The religious situation of Selucia was drastically changed as a result of the Selucian Crusade. Wishing to end Pagan worship in Selucia and to forcefully bring the Selucian Chruch within the fold of the Terran Patriarchal Church, the Pápež launched a Crusade against Selucia, led by the Order of Saint Parnum. The Crusade was successful in taking over Selucia, establishing a military monastic state in 2830. Resistance to the Orderstate was led by Selucian Patriarchals, who managed to overthrow the Crusaders and established a Selucian Patriarchal theocracy in its aftermath. Paganism was outlawed throughout the nation for the first time in its history, marking the culmination of its decline as the Selucian national religion.

Modern times[]

Altar of the Republic in Sadarium, built during Triariist rule

Paganism did nonetheless experience a major revival in the late 30th century. The persecuted Pagans had taken to arms against the Patriarchal theocracy, united under the new ideology of Triariism, a Pagan Nationalist movement campaigning for a return to the early days of the Imperium. The Triariist Revolution of 2988 reestablished Pagan leadership and removed Hosian theocracy, without actually banning Hosianism. This revival was however brief, as by 3163 the Triariists were overthrown, Hosian rule was restored, and the persecution of Paganism continued with renewed fervor. Within the next few centuries, save a few instances of respite, Pagan beliefs and practices were nearly terminated in the nation. By the 37th century the Religio was confined to remote rural areas and amongst impoverished city-dwellers. In this century Paganism experienced another short revival during the Communist revolution led by the Plebeian Democratic Party, which saw the restoration of Paganism as a necessary step towards the dismantling of Patrician privileges. Although the revolution was unsuccessful, it did result in the removal of Paganism's status as religio illicita. The end of official persecution reversed the negative demographic trend experienced by the Religio, although this did not lead to a resurgence on the scale of the Triariist revival.

The Barmenian Refugee Crisis created a new opportunity for the revival of the Pagan faith. The expulsion of crypto-Felinists by the Barmenian government in 3818 determined most Felinists to seek refuge in Selucia. Although they were violently prevented to do so at first, the refugee crisis ultimately led to the fall of the Hosian government in Selucia and its replacement by a Pagan and pro-Felinist coalition. During the Crisis the College of Pontiffs decided that Felinism is a valid expression of the Selucian Religio, leading to a flood of Felinist refugees into Selucia and a large demographic increase in the number of Pagans. At the same time, mystery cults were also accepted as a full part of Selucian Paganism, resulting in a rising popularity of these permissive religious practices, changing the hitherto relatively conservative nature of the Religio.

Government-sponsored procession in honor of Terra Mater during the millennial celebrations in 4811

For the following centuries Selucian polytheism experienced a slow and very gradual revival, but it remained a minority and occasionally persecuted religion. It was the secularization of Selucian society during the centuries-long rule by In Marea that indirectly supported the rise of Pagan worship. The privileges and power of the main rival of Paganism in Selucia, the Aurorian Patriarchal Church, were gradually eroded, ending Hosian dominance. For a time Hosians and Pagans were closely allied under the Republican Party, but after its collapse Pagans once again found themselves the target of Hosian persecution. Hosian rule was eventually ended by the Duodecimvirate that ruled Selucia between 4793 and 4802. The 11th Republic established by the Duodecimvirs was the most favorable to Paganism in millennia, and during its existence Selucian polytheists became a plurality of the population for the first time since the early 30th century. The founding of the 11th Republic was marked by the celebration of 3000 years since the unification of Selucia, the celebration of which included a heavy emphasis on Pagan rites and rituals. Also for the first time in millennia Selucian Paganism was declared the nation's sole official religion.

Divinities[]

The Selucian Religion has a large number of gods and numerous minor gods and spirits. The Religio does not draw a sharp distinction between gods and lesser spirits, and they are all known by the word deus (f. dea, pl. di / deae). For this reason the translation of the word as "god" is sometimes avoided in favor of the Selucian-derived term "deity", or sometimes "spirit".

The deities of Selucian polytheism are divided into many different categories depending on their attributes; categories include the Di Duoni (the divine dead), the Di Inferes (infernal gods, or gods of the Underworld), the Di Consentes (the greater 27 gods), the Di Conservatores (savior gods), the Di Conserentes (gods of procreation), or Di Novensides (foreign gods). These categories are overlapping, as a deity may belong to more than one, and most of these categories include both great gods and lesser spirits dedicated to common everyday activities. For example, Sol Lucidus is considered one of the Di Novensides as his worship is of Qedarite origin, but he is also included among the 27 great gods, the Di Consentes; the Di Inferi include both Aetus (OOC Dis Pater), the King of the Underworld, but also the human dead that reside in it.

The Di Consentes collectively form the official pantheon, which includes 27 main gods, and is known as the Divine Pantheon. The gods are pooled in groups of three each.

- The first group contains the three gods for the state (Di Civiles): Sol Lucidus, Terra Mater, and Neflons who represent the sun, the earth and the water respectively. (OOC: Sol Invictus, Magna Mater, Neptunus)

- The second group contains the three gods for growth, breeding and health (Di Augusti): Genitrix, Iana, and Munius, who represent fertility, hunting, and healing, respectively. (OOC: Ceres, Diana, Aesculapius)

- The third group contains the gods of trade, luck and war (Di Populares): Negotius, Mercuria, and Mamors. (OOC: Mercurius, Fortuna, Mars)

- The fourth group deals with matters of the island of Aquilonia but is also present on the other islands. These gods handle matters of wine (and other alcoholic drinks), crops and manufacturing (Di Ubertatis): Orgius, Nuptia, and Mentia. (OOC: Bacchus, Iuno, Minerva)

- The fifth group deals with matters of the island of Oleria. These gods, also more or less represented in other provinces, handle matters of love and gardens, ethics and sea ports (Di Coniugales): Futua, Ustula, and Clavus. (OOC: Venus, Vesta, Portunus)

- The sixth group deals Sadaran matters, though, as with the other groups, you can also find them on the other islands. Stock farming and death, flowers and gardens as well as of the beginning and ending (Di Initii ac Finis): Aetus, Floria, and Hiatus. (OOC: Dis Pater, Flora, Ianus)

- The seventh division (Di Feri) contains gods for newly-born Divitia, fruits and gardens Pruna, and for woods and mineral springs Turna. (OOC: Ops, Pomona, Feronia)

- The eighth group (Di Consivi) consists of Forcula for homeostasis, Balantes for the willow and herders, and Consivus for the harvest. (OOC: Carna, Pales, Consus)

- In the ninth group (Di Fulminales) are the gods Veltus for the seasons, Setlanus for fire, iron and blacksmiths and Aplus, the patron of herds, musicians and artists. (OOC: Vertumnus, Volcanus, Apollo)

The Di Novensides contain gods such as Terex (of Barmenian origin), Adonius (adopted from Cildania), or Nephris (the adaptation of Irkawan goddess Nefre). Most of these deities are the focus of various mystery cults, and with the acceptance of these cults as valid Pagan practices these gods were granted a semi-official (but not universal) status within the Religio.

Further there are many lesser deities who influence Selucian daily life:

- Laeses (also called Genii Loci) are Selucian deities protecting the house and the family - household gods. They are deeply venerated by Selucians through small statues, usually put in high places within the house, far from the floor. Types of Laeses include:

A Selucian Laes

- Laeses Familiares - family

- Laeses Loci - for a certain place (the family house)

- Laeses Publici - (small) town

- Laeses Compitales - crossroads

- Laeses Paganales - villages

- Laeses Permarini - the sea

- Laeses Rurales - land

- Laeses Viales - travellers

- Duoni are the souls of deceased loved ones. As minor spirits, they are similar to the Laeses. They are also called the Di Duoni, and Selucian tombstones often include the letters D.D., which stands for dis duonis, or "dedicated to the Duoni-gods". The word is also used as a metaphor to refer to the underworld.

- Di Penates or briefly Penates are originally patron gods (really geniuses) of the storeroom and are household gods guarding the entire household.

- Lemures mark the dead spirits in Selucia generally. The good are considered as laeses (see above), the bad as larvae and the neutral as duoni. Lemures are those, which had not gotten an appropriate burial place or had committed criminal offences during lifetimes.

- The Larvae are usually dead spirits of people who haunt and harm. Their appearance is skeleton-like and their effect is similar to the Kalopian nekydaimones. They agonise the dead ones exactly the same as the living persons, which they can cause delusions. A person with delusions is called Larvatus. Because they are spirits of the underworld, Selucian people sacrifice only at night to them.

Practices[]

Priest praying in public

Prayer and Sacrifice[]

The most important practices in Religio Seluciana are prayers and oaths, through which the community or individual seeks the aide of the gods; sacrifices are believed to be useless unless accompanied by prayer, whereas prayers are seen as having independent power. Prayer in Religio Seluciana has a strict formulaic character, whereby it can only achieve its purpose if the correct words are spoken and the divinities are addressed by their proper names. Any omission or change in the text of a prayer is cause for restarting the entire ritual. The purpose of prayer is not the establishment of a personal emotional connection with the divinity, being instead seen as a contractual formula, whereby the two participants, the god(s) and the community or individual, oblige themselves to undertake the actions prescribed by the prayer.

In light of the religion's contractual character, oaths and vows are an important religious practice for Selucian Pagans. An oath (sacramentum) is sworn under the witness and sanction of the deities, and breaking an oath renders one a homo sacer, i.e. a "sacred" or "accursed man", deprived of all civil rights and whom anyone may kill without repercussions.

Another central practice in Religio Seluciana is sacrifice (sacrificium), a practice that renders an object sacer, i.e. dedicated to the gods. Most common forms of sacrifice are grain and salt offerings to the household gods, but animal sacrifice is also widely practiced. In the past even human sacrifice was occasionally performed in times of great trouble.

Priesthood[]

Religio Seluciana does not have an organized priestly class; the priests are elected by the community, often for limited terms, and are seen as magistrates, elected public officials. The highest-ranking priest, and the leader of the Religio, is the Pontifex Maximus, who presides over the College of Pontiffs (Collegium Pontificum), which includes the 27 flamines, the Ustulan virgins, and the other pontifices. Each of the 27 gods of the national pantheon has a flamen dedicated to his or her service; the most important flamines are those that serve the three civil gods (Di Civiles); these flamines, called the flamines maiores, are the Flamen Solaris, overseeing the cult of Sol Lucidus, Flamen Terrestris, overseeing the cult of Terra Mater, and Flamen Neflontialis, overseeing the cult of Neflons. The Ustulan Virgins (Ustules, singular Ustulis) are a female-only priesthood in charge of the cult of Ustula, the goddess of the hearth; the Ustulan Virgins are freed from the social obligations of marriage and child-bearing, and are expected to remain chaste throughout their service so they could fully dedicate themselves to the cult of Ustula. Breaking the chastity requirement was in the past punishable by death.

In addition to the members of the College of Pontiffs, other types of priests are found within the Selucian religion. Augurs (Augures) are in charge of the practice of augury, a form of divination based on interpreting the will of the gods by observing the flight of birds. Haruspices (sg. Haruspex) similarly practice divination by examining the entrails of sacrificed animals.

Domestic worship[]

The senior priest within each household is the pater familias, who has the duty of overseeing the daily cult of the domestic laeses and penates, as well as the di parentes (family gods) and the spirits of the ancestors. His wife, the mater familias, oversees the household's cult to Ustula. All members of the household are obliged to worship the genius of the pater familias.

Mystery cults[]

Orgiastic Mysteries

In addition to public and household worship, Religio Seluciana includes a third component, mystery cults (mysteria), of ancient Kalopian origin. Participation in mystery cults is reserved for initiates (mystae), and the practices and rituals of the mystery cults are not to be revealed to outsiders. The most important mystery cults are the Orgiastic Mysteries, dedicated to Orgius, the god of wine and other intoxicants, the Terekian Mysteries, dedicated to Terek the Bullslayer, a divinity of Brmek origin also part of Felinist Paganism, the Nephrian mysteries, focused on Irkawan goddess Nephris (Nefre), and the Adonian Mysteries, dedicated to Adonius, an ancient Cildanian god. Owing to their secretive nature, mystery cults have often been persecuted, even when Religio Seluciana was the dominant faith in the nation; the Orgiastic Mysteries in particular (Orgia, sg. Orgium) have been accused of being frenzied and indecent rites, with alcohol-induced violent sexual initiations of both sexes, all ages, and all social classes, and an instrument of conspiracy against the state. The name of the Orgiastic Mysteries is the origin of the contemporary word "orgy". A recent ruling by the College of Pontiffs decided that mystery cults are to be considered a full part of the Religio, leading to a rise in popularity of mystery cults and Paganism in general, as well as the faith adopting a more permissive nature.

Foreign cults[]

Historically, many different polytheistic religions were practiced on Selucian territory, and while most of them had their gods reinterpreted as aspects of Selucian deities or were outright incorporated into the religion's pantheon, more firmly established foreign cults, particularly mystery cults, were granted their own autonomous leadership and the maintenance of their own foreign rites. In modern times this status was extended to entire foreign religions with significant practice on Selucian soil, including Felinism, Geraja, and Hosio-Paganism (OOC Christo-Paganism). These foreign religions are governed by their own autonomous Collegia formed of priests and priestesses elected by their community, and although these religions are considered separate and autonomous from Religio Seluciana, they are subject to Selucian laws and the decrees of the Religio's College of Pontiffs.